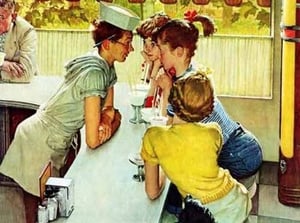

When I was fifteen years old, I worked as a waitress behind the soda fountain at a Norman Rockwell-esque ice cream parlor and homemade candy shop: Conrad’s Confectionery in Westwood, New Jersey.

Conrad’s was a delightful place. The regulars from town met at the counter each Saturday morning: the owners of the jewelry shop and the shoe store, the undertakers from the local funeral home, and the boy I had a crush on from the record shop. I grew confident in my skills and familiar with all the regulars’ names. I could make an excellent ice-cream soda, pour the perfect egg cream and keep the dishes washed and put away -- even when it was busy.

I was on my game and confident.

My boss was a jolly, sixty-year-old man named Jimmy. He ran the store with his wife, Irene, who was usually found tending customers from behind the candy counter. One rule was paramount. Jimmy reinforced it regularly, and I trained all the new employees to follow it strictly. At the end of the long counter, beneath the cash register, was a trap door. The door led to a room below us, where the ice cream was freshly made. When they were ready to send up a bin, the folks making ice cream below would knock on the trap door. At the first knock, we would stop what we were doing, open the door, take the new bin and shut the trap door immediately.

My boss was a jolly, sixty-year-old man named Jimmy. He ran the store with his wife, Irene, who was usually found tending customers from behind the candy counter. One rule was paramount. Jimmy reinforced it regularly, and I trained all the new employees to follow it strictly. At the end of the long counter, beneath the cash register, was a trap door. The door led to a room below us, where the ice cream was freshly made. When they were ready to send up a bin, the folks making ice cream below would knock on the trap door. At the first knock, we would stop what we were doing, open the door, take the new bin and shut the trap door immediately.

The rule was clear: Always shut the trap door before moving on to a new task.

One bright Saturday afternoon, I was the only waitress bustling about serving ice-cream and coffee. I heard the familiar knock and quickly responded. Just as I lifted up a new bin of mint chocolate chip, a customer came in and shot me a smile. Taking pride in the fact that I knew his order by heart, I headed straight for the coffee pot. I had just started to pour, when Jimmy whizzed past me, chatting up the customers at the counter and walking backwards to the cash register to ring up someone’s purchase.

My heart leapt. “Jimmy!” I shouted. “Stop!”

It was too late. Jimmy had fallen in the trapdoor and was wedged between the basement and first floor thanks to his plump Santa’s belly. Two men lept from their stools and bounded round the register. I dropped the coffee cup and dashed to help.

Three of us hoisted him up. Irene rushed from behind the candy counter to see what the commotion was all about.

As Jimmy sat on the ground breathing heavily and clearly in pain, I stood mutely to the side.

Jimmy was alive but I was dying inside.

Irene shot me a look that finished it for me. I watched Jimmy speak weakly to her. She returned to the candy counter, grabbed her purse and enlisted a customer to help her accompany Jimmy to the car. Then she paused. Something softened. She walked right over to me, and said, “Karen, I need to leave you in charge of the store. I will be back as soon as possible.”

In the wake of my horrible mistake, she handed me more responsibility. Somehow, she trusted me with a second chance.

I closed the shop at the end of the day and slunk home to tell my parents what had happened. Then I called Jimmy at home.

“I am so sorry, Jimmy. It was all my fault. How are you?”

“I’m all right, just a few bruised ribs. Thanks for calling. I know you know what to do. I have confidence in you.”

I had blown it -- and he still had confidence in me.

Jimmy and Irene taught me something powerful that day. Their legitimate first reaction -- pain, anger, worry -- was transformed into a very different response: I trust you. I have confidence in you. Their kindness and calm under the circumstances taught me more about leadership than any Harvard Business Review article: they showed me that greatness is revealed in how we choose to respond to stress.

I had known that Jimmy worked at Conrads when he was in high school. Perhaps that gave him some empathy for me as a high school kid. But when I read his obituary years later, I learned that Jimmy served as a Master Sergeant with General Patton's Third Army in WWII shortly after high school. He was awarded the Bronze Star for heroic service.

Jimmy knew firsthand the kind of leadership and greatness young people were capable of: he had served and been demanded of on a grand scale. He wasn’t simply giving me a second chance. He was helping me to envision a new possibility.

It’s so tempting for us to do things for teenagers -- from making their bed to writing their college essay. We care. But precisely because we care, let’s press pause and make space for them to gain experience.

As a veteran educator, I can tell you that there is perhaps nothing that makes a young person grow and flourish more than authentic responsibility and trust.

Ownership of a task, the knowledge that other people are counting on us to carry it out, and the opportunity to learn from (not be crushed by) our mistakes-- these inspire confidence in deep and abiding ways. Kids need to be needed. Let’s keep that real for them and nurture their resilience, even when they blow it.

©️ Dr. Karen E. Bohlin, LifeCompass Institute

Picture credit: Normal Rockwell's “The Soda Jerk” – Saturday Evening Post Cover, August 22, 1953